Life at workIntroductionThere was no such thing as an ‘easy job’ for most working class people in the nineteenth century. All occupations and trades were subject to the same long hours, low pay and what we would consider dreadful working conditions. However, perhaps one of the worst industries to be involved in was coal mining. Not only was the work long and hard but it took place in an inherently dangerous environment. Every year hundreds of people were injured and killed by accidents in mines. Crook was primarily a coal-mining town: the industry was certainly responsible for employing the vast majority of the town’s inhabitants. As a result, we’re going to have a look at some aspects of life at work down a pit.  Image 2: Photograph showing a group of miners, including boys, with a pit pony. (Photo from Durham County Record Office, ref D/Cl12/88) Click on image to enlarge.  Image 3: Extract from the evidence of John Otterson to the Royal Commission into the Employment of Children in Mines. (Image from Durham County Record Office, ref Library G249). Click on image to enlarge.  Image 4: Extract from the evidence of William Laws to the Royal Commission. Unusually, Laws still attended Sunday School and mentions playing games. Click on image to enlarge. Dangerous workCoal mining was, and remains to this day, a very dangerous occupation. The miners were at risk from flooding, poison gas, fire damp (an explosive gas), accidents using the machinery and from pit collapse. Preventative measures were taken but they were of limited value. Pumps were installed to remove water from mines but these could not cope with a sudden influx of water; basic ventilation systems such as the use of trap doors helped to stop pockets of poison gas developing; miners took canaries down the mines with them knowing that the bird would be affected first by any toxic fumes; Humphrey Davy’s safety lamp, introduced in 1815, considerably reduced the risk of explosions; and wooden pit props were used to support the weight of the mine above, although these often failed. According to statistics taken from the Mines Inspectors’ Reports, over 90,000 people were killed or injured working in coal mines in the UK between 1850 and 1914.

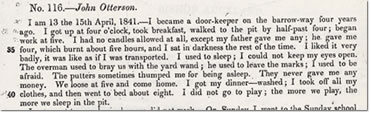

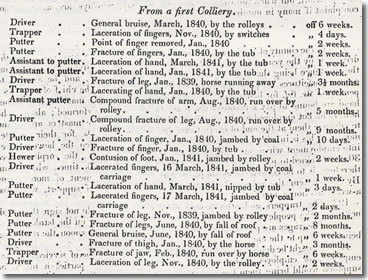

Nor was it just adults that were at risk when working down the mines; the extract from the Royal Commission report shows the type of injuries sustained by children.

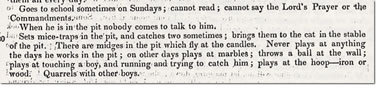

The consequences of sustaining an injury or dying were very great indeed. This was especially the case when it was the main breadwinner, normaly the husband or father, who was involved. There was comparatively little employment for women in coal mining districts and families were therefore dependent on what the male members brought home. In a time before any kind of official welfare relief (other than the Poor Law) was on offer, any reduction in earnings had severe ramifications. When major disasters occurred, relief funds were often set up to provide some sort of temporary assistance but this was of limited help.  Image 1: Late 19th century photograph showing some Durham coal miners. (Photo from Durham County Record Office, ref D/Ph162/8.) Click on image to enlarge. Children and coal miningWhen people think of coal miners they tend to have an image of muscular men with faces and bodies blackened from the coal dust. However, it was not just men who worked in mines but women and children too. The 1842 Royal Commission into the Employment of Children in Mines found that children as young as five or six were working full days in some mines. They were mainly employed as trappers or door-keepers. This job involved opening doors so that the trucks carrying the coal through the mine could pass through and then making sure they closed behind them. It was essential that this was done so that the mine remained properly ventilated. Although not physically hard, the work was boring and was often done in complete darkness. As the children grew older they were sometimes moved on to opening the barrow-ways (larger openings designed to allow larger trucks and sometimes ponies through) before starting work actually moving the coal. The Commissioners were deeply shocked by what children were asked to do in the mines. They found that girls as well as boys were expected to haul and push trucks weighing up to 200 kilos through the mine, work which caused deformities and long-term injuries. In response to the findings of the Royal Commission, Parliament passed the Coal Mines Act of 1842. This banned all women and children under the age of ten from working underground and prevented anyone under the age of 15 from working the winding machinery. Although children could still be employed above ground, the Mines Act was at least a start in offering them some protection. Despite the terrible working conditions, few children complained about having to work. Most recognised that the few pence that they earned each day helped their families survive. However, it also meant that they missed out on the already limited opportunity to gain some education and were given very little chance to play as children today do.

Image 5. Images depicting a design for a safety suit to ‘penetrate dangerous gases’. Taken from T.Y. Hall, A Treatise on the Extent and Probable Duration of the Northern Coalfield, (Newcastle, 1854). (Image from Durham University Library, ref XL 553) Click on image to enlarge.  Image 6. Examples of injuries sustained in one colliery in the North East. Taken from the report of the Royal Commission into the Employment of Children in Mines, 1842. Click on image to enlarge. |