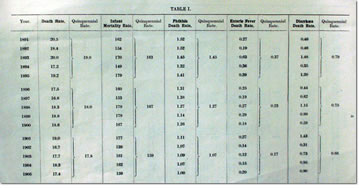

Health and sanitationHealthTowns and cities were incredibly unhealthy places to live in the 19th century. Rapid industrialisation had resulted in equally rapid urbanisation. Houses were built quickly to accommodate the growing workforce and little, if any, thought was given to planning. Many of the houses were very poorly built, with little ventilation, and most suffered from damp. No thought was given to ensuring adequate sanitary provision. Toilets, washing facilities and even drinking water were often communal. All in all, it provided the perfect environment for the spread of disease. Life expectancy actually fell for many people in the 19th century. The average life span of an industrial worker in 1871 was less than 45 and three out of every twenty children died before reaching the age of one. Durham was nor immune to the effects of industrialisation and urbanisation. A report into the sanitary conditions of the City of Durham in 1847 found that drainage, sewerage and ventilation were so bad that the city could no longer remain indifferent to it if they valued life and health above money.  Poster warning of the dangers of cholera and precautions to be taken against it. (Image courtesy of Durham County Record Office, ref D/Ph191/3) Click on image to enlarge. Public Health ImprovementsSporadic attempts to improve public health were made throughout the 19th century. The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 reformed local government, establishing town councils with members elected by ratepayers. The councils were in charge of their own district but both the majority of councillors and ratepayers preferred low rates to costly investment in improving sanitation. The first Public Health Act of 1848 allowed local boards of health to be set up and medical officers appointed but this proved unpopular. It was not until the 1870s that any real change could be noticed. By this time it was clear that poor public health did not just affect the poor but also the rich. Plus the 1867 Reform Act had given more working class men the vote and, therefore, more power. In 1872 a further Public Health Act was passed which made the appointment of medical officers compulsory and allowed sanitary authorities to be set up. The latter was made compulsory by another Public Health Act of 1875. These measures, combined with a rise in civic pride, slowly led to the improvement of many towns and cities. Sewer systems were built, water supplies improved, slum areas cleared and new housing regulations brought in.  Photograph of late 19th or early 20th century housing in Durham city centre. (Image courtesy of Durham University Library, ref Gibby A/CIT/92) Click on image to enlarge. CholeraThe first ever cholera epidemic in the British Isles started in Sunderland in the autumn of 1831. The disease had spread from India to Baltic ports like Danzig, Hamburg and Riga. There was lively trade between these ports and Sunderland, so it was no surprise to the newly created Board of Health when the first suspected cases were found in Sunderland, even though they did not know how the disease was spread. The first victim was Ellen Hazard, a 12 year old girl from Low Street, Sunderland who was buried on 19 October 1831. The epidemic spread through Tyneside and then on to the rest of Britain. 32,000 people died in Britain, the result of a global pandemic that killed millions. Further outbreaks occurred in 1848, 1853 and 1866, each time causing thousands of people to suffer a painful and unpleasant death. At first, doctors had little idea about what caused cholera. It was thought that the disease was carried in the air, but all kinds of precautions were urged. The link between cholera and contaminated water was not proved until 1854 when Dr John Snow (who had first experienced the disease whilst working in the North East) discovered cholera in a well that had been contaminated by a cess pit.  Entry from the Sunderland burial register showing the entry for Ellen Hazard. (Image courtesy of Durham County Record Office, ref EP/Su.HT1/102) Click on image to enlarge  Table showing the reduction achieved in the death rate and infant mortality rate in Co. Durham as a result of various public health improvements. Taken from A Brief Survey by the Chief Medical Officer of Health. (Image courtesy of Durham University Library, Pam L+352.4 DUR) Click to enlarge. \ |