The History of Durham Prison

Durham Prison is one of the most famous in the country. It has been the home of some of Britain’s most infamous criminals over the years, including Rose West, Myra Hindley, the Kray twins, John McVicar and Frankie Fraser. It is also the resting place of a number of men and women executed and buried in its grounds. Durham has had a number of prisons built within the city walls over the years and the current prison is one of the city’s best known landmarks. Before the building of the present Durham Prison there were two prisons in the city. One was the County Gaol in Saddler Street and the second was the old Bridewell or House of Correction which was built under Elvet Bridge. The County Gaol was owned by the Bishop of Durham and was rebuilt in Saddler Street in the early 15th century. It was enlarged in 1773 but was still very cramped. It was visited by a number of concerned individuals over time. This included John Howard, the leading prison reform campaigner, who made repeated visits because he was convinced that the gaoler was trying to cover up the bad conditions that prisoners lived in. Another reformer, James Neild, published his findings in the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1805. As well as witnessing the primitive conditions of Durham Gaol, Neild also recounted how his visit nearly cost him his life. He had nearly fallen down a deep shaft whilst exploring a dungeon and he was only saved when his coat caught on a nail. Needless to day, Neild was not impressed by his experience! Durham Gaol was also visited by Joseph Gurney and Elizabeth Fry as part of their tour of prisons of England and Scotland. What is like to be a Prisoner ?In a word, awful! Before the 1823 Gaol Act, the warder had to pay for the right to run the gaol and made his money back by charging prisoners for their food, drink and ‘other services’ he provided. These services included releasing prisoners, providing straw for bedding and even providing drinking water! Durham Gaol also had a licence that allowed one of the warders, Bainbridge Watson, to sell alcohol and part of the gaol was used like a pub! There were different rooms for debtors (people imprisoned because they owed money to others and who would not be released until it was paid) and felons (criminals and people awaiting trial in court). However, little attempt was made to keep the felons separated so innocent people awaiting trial mixed with murderers, convicted criminals awaiting execution and those waiting to be transported as punishment for their crimes.

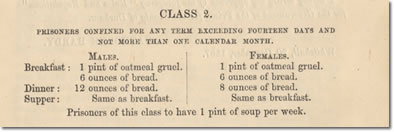

None of the prisoners had an easy time. In 1776 the felons were given rations of 1 pound of bread per day and nothing else. Debtors ate water soup, which was bread boiled in water, and whatever foodstuffs had given from well-meaning people making charitable donations. So bad were the conditions endured by debtors that they even appealed to Parliament for better food and clothing saying they wore rags and had nothing to eat.

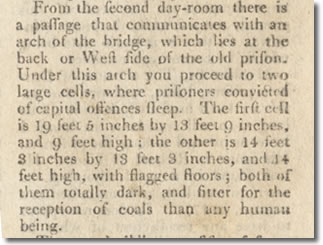

Durham County House of Correction (the Bridewell) was no better. Built in 1634 on the north side of Elvet Bridge it was originally set up to help reform idle vagrants by providing work and accommodation in a place of punishment but it soon started to serve as a common prison for felons just like the County Gaol. There wasn’t much difference between the two and there were times when they were both run by the same people. Described by Nield as being ‘fitter for the reception of coals than for any human being’ conditions here were just as bad as at the County Gaol, although there were rooms for people to work and anything the prisoners earned could be kept to pay for food and drink. It too was home to a variety of debtors, felons, transportees, men being forced to join the army or navy instead of being executed, those awaiting execution and a collection of lunatics and vagrants who couldn’t be put anywhere else. Find out about the building of the new prison in Durham in the next section.

|

Picture of a reconstructed prison cell. Image courtesy of Durham Heritage Centre.

Male and female prisoners were separated but conditions were no better for either sex. At night the felons were put into 5 cells deep in underground dungeons that were badly lit and ventilated by the few holes in the ceiling. These were described by Neild as the ‘worst cells in the country.” Women also both lived and slept in the same room in foul conditions.

The smell would have been foul as there was no sewer and the rubbish and waste wasn’t removed very often. Cells were overcrowded and the felons lay on beds of straw and some mats infested with bugs and insects. Rats would have been a common sight, the filth encouraging their successful breeding. It was a place where the strong bullied the weak and any new inmate could expect to have their few possessions stolen and sold on for food and water. There was usually nothing for the inmates to do except swap stories of their great exploits and plot future crimes and escape plans. In his inspection of 1803, Neild did find prisoners spinning, picking oakum and beating flax but later inspections by Gurney found no evidence of such work being given to prisoners. The gaol was just too small to have space where the inmates could work.

Extract from the Prison Rules of 1865 showing the typical diet of Class 2 Prisoners. (DUL ref: L 365.6 HM)

Extract from the Prison Rules of 1865 showing the typical diet of Class 2 Prisoners. (DUL ref: L 365.6 HM)

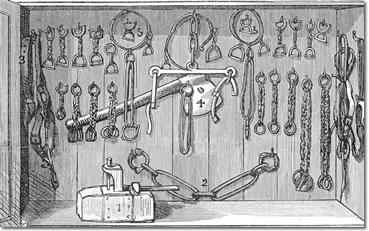

The foul conditions meant that there were frequent attempts to escape but if caught, prisoners faced being clamped in irons – as did those who knew anything (or even nothing) about the escape attempts. When Howard visited he found men who had been chained to the floor for many weeks, which had ‘twisted their bodies cruelly and caused great pain’ to them. Even worse, in 1818 Gurney found every prisoner in irons because of an escape attempt on the previous day. Gaolers were penalised if anyone escaped plus they were able to extort more money from the felons for removing the irons. Only with the introduction of paid gaolers and the campaign for prison reform did the situation start to improve.

Photograph showing the entrance to the old Bridewell, now a bar.

The New Prison

The new prison was founded with £2000 paid by Bishop Barrington Shute of Durham who wanted to be rid of the existing gaol which he felt was a traffic hazard. In 1808 Sir George Wood had commented on the poor state of the House of Correction and County Gaol and so moves were made to build a new prison to replace these. With great ceremony the construction of the current prison began on 31st July 1809 when the foundation stone was laid by Sir Henry Vane Tempest. Large crowds attended to see the Bishop place gold, silver and copper coins of the time into the foundations, bands played and soldiers from the Durham volunteers fired a volley of shots with their rifles to celebrate the occasion but because of problems in its construction, no prisoners were transferred to the new prison until 1819. Indeed, the first architect, Francis Sandys, was jailed for theft of money in building the prison, the plans were heavily criticised and some parts even had to be pulled down and rebuilt. When it finally opened the new prison had 600 cells and was able to replace both the old House of Correction and the County Gaol. Some prisoners have claimed that the new prison is haunted – saying they have seen something in a cell where one inmate was allegedly stabbed to death by another.

Front page of the 1819 Rules for the Governance of Durham Gaol. (DUL ref: XLL 942.8)

The prison operated a series of punishments for various misdemeanours. This included fettering in irons, flogging, birching, the treadmill and close confinement. The treadmill was introduced as a punishment when a prisoner had severely brokem the prison rules. They were expected to turn the treadmill by walking on it. Each turn was counted and 500 turns was considered a good day’s effort. However, as the prisoner became accustomed to the treadmill it became easier for the prisoner to turn so a special screw was introduced which the prison turnkeys could use to adjust the pressure and make it more difficult to turn. This is why prison officers are still known to this day as ‘screws’.

Photograph showing Durham Prison. Image courtesy of HM Prison Durham and John Cavanagh.

The new prison needed new rules which reflected the changes in attitude to punishment and criminals. After 1819 male and female prisoners were kept apart, as were debtors and felons. Rules forbade drinking, bad language, disobedience, quarrelling and indecency. All prisoners were to be put to work with some being paid for their work when they were discharged. The prisoners were classified and separated according to the crimes they had committed and work was expected to help in reforming the character of these people. Short term offenders had to take away rubbish, level ground, extend gardens whilst longer term prisoners had to pick oakum, work in the workshops etc. Considerable efforts were made to find suitable work for every prisoner but bad weather sometimes made this difficult. In 1820 Visiting Justices were appointed to inspect the prison 3 times every quarter of the year to ensure that standards were acceptable.

Engraving from the London Illustrated News showing chains in use at Newgate prison. (DUL Ref + 050 v093 1888)

In the next section we take a look at the history of executions that took place in Durham.