WeaponryPractically every infantryman serving in the First World War was issued with a rifle. The Germans had the Gewehr 98 Mauser Rifle, the French had the Lebel or Berthier Rifle, the Russians had the M1891 three line rifle and the British had the .303 Short Magazine Lee Enfield. All these actions were bolt action rifles, capable of firing ten or more rounds per minute. Although all the rifles used by the different armies were capable of firing up to 2000m, they were not really effective at this range. To inflict real damage meant firing at much shorter distances. Under the British system, ‘close range’ was defined as less than 600m, ‘effective range’ at 600 to 1400 m and anything longer than that was classed as ‘long range’. Rifles were very powerful. Most of the models used in the First World War were capable of penetrating half-inch steel at very close range or were able to cut through a brick at 200 yards. However, the amount of damage caused to a person depended not only on the range but how and where the rifle entered the body. Stories of bullets going straight through arms, legs or even heads without causing death or serious injury were not just apocryphal.

Photograph showing Macfarlane Grieve training in use of machine gun. (DUL ref: Misc Photo Album 2)

Photograph showing a training session in the use of machine guns. (DUL ref: Misc Photo Album 2)

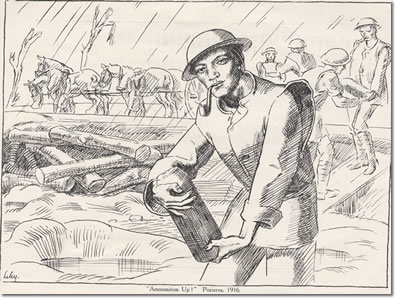

Trench warfare changed the way in which battles were fought. No longer could the enemy be attacked out in the open as they were protected by their dugouts. The only way of achieving any kind of success was to destroy the trenches themselves. This meant using shells and other kinds of heavy artillery. However, this was not as easy as it sounded. Most of the countries engaged in the War suffered from serious problems in supply – the munitions factories simply couldn’t keep up with demand. In Britain, the ‘shell scandal’, as it was known, ultimately led to the fall of the Liberal government and the establishment of a Ministry of Munitions led by Lloyd George. Although production of shells and other artillery increased after the shell scandal, the British Army still faced a number of serious problems. First, the vast majority of shells produced were shrapnel shells rather than the big high explosive shells which were needed to actually damage the trenches. Secondly, many of the shells were poorly designed, some exploding in the gun itself causing many injuries and deaths. Finally, a lot of shells were so poorly produced that they failed to explode on impact. It has been estimated that in the Battle of the Somme between one quarter and one third of the shells fired by the British failed to detonate.

Extract of report focusing on the use of trench mortars. (DUL ref: Lowe Papers)

Photograph showing section of 4th Highland Light Infantry. (DUL ref: Misc Photo Album 2)

Herbert Maxim had developed a machine gun in the mid-1880s but none of the future combatants had embraced the concept whole-heartedly. This was mainly due to the fact that the early machine guns were very heavy, hard to manouevre, prone to overheating and, perhaps most importantly, they were expensive. The result was that in 1914 the British only had two machine guns to each battalion, and the Germans six per regiment. However, it was not long until their usefulness was recognised and numbers rapidly increased. The main, and obvious, advantage of machine guns was the amount of rounds that could be fired. The Maxim gun was theoretically capable of firing 600 rounds per minute, although it tended to achieve about 300 in the field. Although the German Army were able to increase production of machine guns before the Allies it was not long before they caught up. By the end of 1915, the British Army was using the lighter Lewis gun in addition to the Vickers machine gun and had set up the Machine Gun Corps to provide specially trained gunners. The result was that by 1917 each infantry section had a Lewis gunner and a battalion had 46 Lewis guns at its disposal.

Drawing of a member of 142 Heavy Battery with a shell. (DUL ref: Add MSS 1584)

Mortars were particularly useful in trench warfare. Basically they consisted of a tube that could fire objects at a steep angle into the enemy trench. Lighter and more manoueverable than traditional artillery pieces, mortars also had the advantage of being fired from within the trench making them safer to use. The Germans had recognised their potential even before the war began and had managed to accumulate a stockpile. In contrast, the British had no such weapon until 1915. However, once in use the British realised its full potential and, with the invention of the Stokes mortar in January 1915, developed the best system. Mortars were very effective at hitting trenches and were often used to take out particular sections, such as a Machine Gun section, or to cut barbed wire. Grenades were also used for attacking trenches and, again, proved very effective in this role. As an attack neared an enemy trench, bombing parties would run along the trench throwing in the grenades to clear them. Throughout the war there were two main kinds of grenade: percussion grenades and timed fuse grenades. The former, which exploded on contact, were not very popular as they were prone to going off when knocked so both sides made greater use of fused grenades. Once again, it was the Germans who made the earliest use of grenades. Britain did not start to mass produce grenades until 1915 and it was not until the introduction of the Mills bomb in that year that they were able to keep up with the Germans. It has been estimated that over 70 million Mills bombs, and 35 million other types of grenades were used by the Allies alone in the course of the war. |